How a gunfight in New Orleans over pasta production, and the assassination of a New York police officer, were related to counterfeiters in upstate New York.

Antonio Comito was the captive printer, forced by Morello’s gang to produce counterfeit bills at their Highland, New York farm, the winter of 1908-09. Introduced by “Don Pasquale” (most likely Vasi, one of two brothers found guilty for their participation in the counterfeiting operation) in New York City to Don Antonio Cecala, as a prospective printer for Cecala’s Philadelphia press, Cecala in turn introduced Comito to Cecala’s godson, Salvatore Cina. Cina, Comito, and a cart driver, Nicholas Sylvester, shopped in New York for a printing press, then left the city. Instead of taking Comito and his companion, Katrina Pascuzzo, to Philadelphia, as discussed, they went to Cina’s 42 acre fruit farm in Highland, across the Hudson River from Poughkeepsie. Cina’s brother-in-law, Vincenzo Giglio, was at the farm when they arrived.

Someone called Uncle Vincent (possibly Giglio), who said he raised cattle in his hometown, stayed with them that winter. He told Comito of killing two men, then fleeing, first by train to Palermo, then sailboat to Tunis, and from there to Tokyo and then Liverpool, before making his way to New Orleans in March 1902.

New Orleans was the first city in America to have a Mafia presence. In 1894, when the Morello-Terranova family went south, looking for work, they made contacts among local mafiosi. A so-called “cousin” got Giuseppe Morello and his stepfather work in sugarcane country; he may have been Antonino Saltaformaggio, an early immigrant from Corleone who would marry Morello’s half-sister. Given Antonino’s youth—he was just twenty at the time—Morello’s most important contact may have been Antonino’s father, Serafino.

Giuseppe Morello and Antonio Saltaformaggio, each of them an eldest son, were at least the second generation of mafiosi in their respective families. Morello was an active Fratuzzi member in Corleone, as was his stepfather, Bernardo Terranova. Saltaformaggio has two maternal uncles who were active in the Fratuzzi, in the years after his death. When his body was identified, the local newspaper pointed to his mother as the source of trouble for the slain man.

***

Lucia Terranova was seventeen when she left Sicily for the first time. She came to the United States with her parents and younger siblings, following her older half-brother, who was fleeing arrest. “Piddu,” as his family called him, was implicated in one murder in Corleone and his companion in flight, Gioachino Lima, was wanted for another. Lima would later marry Giuseppe and Lucia’s sister, Maria Morello.

It was March 1893, when Lucia and her family met up with Giuseppe in New York City’s East Harlem, where many immigrants from Corleone lived. Along with Lucia and her family, were her sister-in-law, Maria Marsalisi, the wife of Giuseppe, and their first child, a son born after Giuseppe’s flight, and named after his late father, Calogero.

The family was unable to find work in New York, due to the financial crisis, so in January 1894, Morello went on a scouting mission to Louisiana, while Bernardo Terranova and his young family stayed in East Harlem: the Terranova brothers were still children, ages four through nine. In February, Lucia Terranova married Antonino Saltaformaggio in Plaquemines Parish, Louisiana.

It would have been most correct for Serafino to have met with Bernardo Terranova in person to arrange a marriage between their two children. Based on the known timeline, the decision appears to have either been made quickly, in Louisiana, or else at great length: perhaps arranged years ago in Corleone, or during the Terranova family’s year in New York. If Bernardo was unable to travel, Serafino and Giuseppe—and possibly the groom, Antonino—may have made the arrangements.

The Morello-Terranova family only stayed in Louisiana for about a year before moving on to a new opportunity, farming cotton in another community of transplanted Corleonesi, in Bryan, Texas. Most likely, Lucia stayed in Louisiana with her new husband, whose parents and siblings lived in the area.

***

Serafino, age 52, died in 1899 on a sugar plantation in Poydras, Louisiana, in St. Bernard Parish. His widow, Caterina, appears in the federal census the following year, living in the same parish with two sons and three daughters, including Teresa, who married Santo Calamia in 1901. The marriages between Lucia and Antonino, and between Antonino’s sister, Teresa, and Santo Calamia, bound Giuseppe Morello and the Calamia men in a relationship which Santo would later abridge to brothers-in-law.

Santo Calamia was born in 1875 in Gibellina, Sicily, due west of Corleone, in Trapani province. In Santo’s case, as well, the evidence suggests that Mafia activity ran in the family. It’s not known when his father, Giuseppe, arrived in the United States, but Santo claims to have arrived in 1889. Father and son lived in New Orleans for many years, although Giuseppe returned to Gibellina by 1909.

A Mafia boss, Francesco Genova, fled Sicily, detouring in London and New York before arriving in New Orleans in 1902. On the strength of his criminal reputation, he soon came to rule the Sicilian underworld of New Orleans.

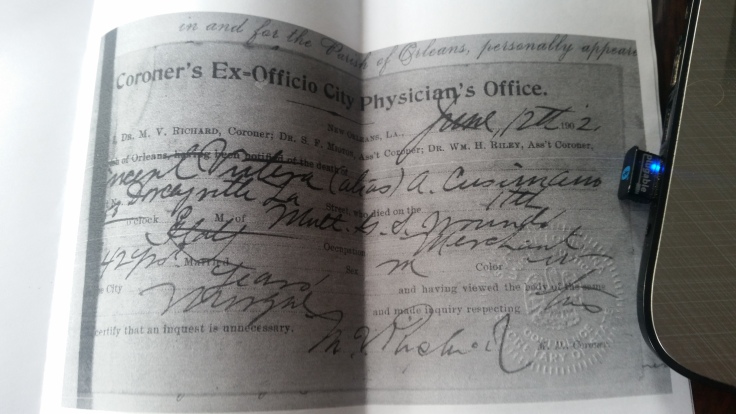

Because of the large Sicilian population in New Orleans and the surrounding area, macaroni was becoming a big business. Stores serving neighboring sugarcane plantations stocked the versatile product among other basic provisions. The largest, most modern macaroni factory was built in New Orleans in 1902 by Jacob Cusimano, of Palermo.

Using agents, Genova attempted to take over a macaroni factory in Donaldsonville, in northeastern Louisiana, on the Mississippi River. “Factory” indicated manufacture at any scale; many macaroni factories at this time were run out of homes and other businesses, such as from the backs of groceries.The factory in Donaldsonville must have been one of the larger operations, to be worthy of a takeover war.

A duplicitous partner in the venture, backed by Genova, was called Paolo (or Charles) Di Christina, an alias for Francesco Paolo Marchese. A letter found in Giuseppe Morello’s possession, from Genova, recommended Marchese to Morello as a fine young man.

The legitimate owners of the Donaldsonville factory, Antonio and Salvadore Luciano, fought back against Genova, but were unlucky enough to miss at close range. When Genova and Di Christina failed to appear in court for a hearing related to the Luciano brothers’ unsuccessful attack, they prepared themselves for a vendetta. They did not wait long.

In May 1902 Santo Calamia, along with Genova, Di Christina, and Joseph Geraci, stormed the Luciano brothers in their “dingy” storefront on Poydras Street. Vincenzo Vutera, who was also killed in the attack, may have also been a Genova plant. Vutera is reported by one witness, a Luciano cousin, to be the first to respond to the attack, firing in their direction with a pistol. According to other accounts from inside the store that night, Vutera—who is described as recent Italian immigrant weighing “fully 800 pounds,” also in the macaroni business—mortally wounded Salvadore Luciano, himself, and was seen doing so by the man’s brother, Antonio.

The record of Vutera’s death cites multiple gunshot wounds, and the news reports that the “big man” continued firing at the invaders, even after he was shot. After the Genova party left, as Salvadore lay dying, people in the street could hear a final shotgun blast: Antonio Luciano’s revenge for Vutera’s treachery. By their exchanges in the police station, Luciano clearly held Calamia responsible. Calamia and Genova were charged with the Luciano and Vutera murders, but acquitted.

A year after the Luciano shooting, Santo Calamia’s brother-in-law, Antonino Saltaformaggio, was killed. Antonino worked, at the time, in cotton country as “a kind of labor agent,” and made his home in the same northern town as the Luciano brothers’ coveted macaroni factory. His body was found on 7 April 1903 near White Castle, about ten miles upriver. He had been stabbed nine times, and strangled with a rope, then thrown into a canal. Another victim, never identified, was killed not long before him, in the same area.

Weeks after his body’s discovery, when the victim was finally known, the news mentions Saltaformaggio’s wife and infant son, left behind in Donaldsonville, but not by name, and no connection is drawn to the Morello-Terranova family of New York City. Instead, the Times-Picayune points the finger in the direction of Antonino’s widowed mother and siblings, living in New Orleans, as the probable cause of the violence against a well-liked and hard working young man.

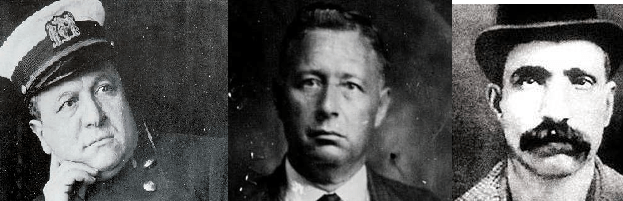

A week later, the body of a Buffalo, New York stonemason was found in a sugar barrel, in New York City. Police detective Joseph Petrosino investigated the crime. The “Barrel Murder” victim, Benedetto Madonia, who was originally from Lercara Friddi, was discovered to be part of a “secret society,” of which Giuseppe Morello was also a part. Vito Cascio Ferro, who was also known to police as a counterfeiter, was among the men brought in on suspicion of the murder.

After her husband’s murder, Lucia Terranova reunited with her family in New York City. The young son mentioned in the news did not go with her. Descendants of Santo Calamia tell me he was named Serafino, after his paternal grandfather, and called “Joe Fino.” I have not found any vital records for Lucia and Antonino in this period, or evidence of any children. (It is notable that in ten years of marriage, Lucia and Antonino had just one child. Lucia had six children in eleven years, in her second marriage.)

In December of that year, three of the Morello-Terranova siblings married, including Lucia, to an associate of her brothers, Vincenzo Salemi. His sister, Lena Salemi, married Giuseppe, who was a widower of eleven years by this time. Ignazio Lupo married Lucia’s sister, Salvatrice.

A 1905 census records Giuseppe Morello in close proximity to the Lo Monte brothers, who were among his closest criminal associates. In this state census, Morello lives with his wife and two children, (one from his first marriage), and calls himself a salesman. Morello was a counterfeiter in 1903, but he also had other ventures, legal and illicit, and whether he continued counterfeiting in those years is not certain. His building cooperative was active and seemingly legitimate in the years after his second marriage. However, in 1907 there was another banking panic, and the Ignatz Florio Building Co-op changed its tactics, a move that more closely aligned them with a growing network of Mafia families in the United States, and at the same time distanced the Co-op from the support of the local Sicilian community. Morello began dipping into the cash reserves of the already strained business.

In 1908, Comito was taken to Highland to print counterfeit bills on Cina’s farm. While he was there that winter, New York homicide police lieutenant Joseph Petrosino was murdered in Palermo.

In February 1909, Petrosino went to Italy to retrieve the criminal records of Italians in the United States, so they could be arrested and deported. The trip was supposed to be confidential, but one of his superiors leaked it to the press.

That month Giuseppe Palermo, introduced to Comito as “Uncle Salvatore,” (Palermo was also known as Salvatore Saracina) and Ignazio Lupo visited the Highland farm. The conversation among Uncle Salvatore, Ignazio Lupo, and the others who showed up on 12 February 1909 (Cecala, Cina, and Sylvester) strongly suggested that Morello arranged to kill Petrosino while he was in Sicily.

Morello was not the only one implicated in Petrosino’s shooting. Vito Cascio Ferro was also suspected of involvement, because the New York police lieutenant had arrested him in connection with the “Barrel Murder,” in 1903. In one version of events, Cascio Ferro left a dinner party, took his host’s coach into the city where he met Petrosino in a public plaza, shot him, and returned to the party; his host supplied Cascio Ferro with an alibi. Other accounts of the assassination have two gunmen, fleeing the scene. The case was never officially solved.

After Petrosino’s assassination was announced in the news, the Highland counterfeiters discussed the crime again in Comito’s presence. Uncle Vincent said something Comito considered significant, that because Petrosino was killed in Palermo, that “it was well done.”

Santo Calamia’s father, Giuseppe, living in Gibellina, was also wanted by Italian police, as an accessory to the Petrosino shooting. Calamia fled Sicily via London and New York, before being arrested in New Orleans, very near his son’s address on Poydras Street. Reporting at the time indicates his family and close friends were hiding him with the intent to send him to the west coast.

The following winter, Giuseppe Morello and his associates were arrested and found guilty of counterfeiting. Antonio Comito, the captive printer, testified against them. Morello was sentenced to ten years in the federal penitentiary in Atlanta.

Santo Calamia visited Giuseppe Morello in prison in Atlanta four times between 1917-20; in the visitor log, he calls himself Morello’s brother-in-law. Santo’s father, Giuseppe Calamia died in 1921 in Gibellina, and Santo applied for a passport soon after, to settle his father’s estate and arrange for his burial.

He never made it back from Sicily. Santo died in his native town the following spring.

Sources

Babin, D. (2015, April 28). Bumped Off On The Bayou: The Macaroni Wars.

Jon Black at Gangrule, “The Morello and Lupo Trial.”

Comito’s Story. (2010, April). Informer: The History of American Crime and Law Enforcement. April 2010. Pp. 5-17.

David Critchley’s The Origin of Organized Crime in America: The New York City Mafia, 1891-1931.

The Murdered Italian Found at Whitecastle. (1903, May 7). Times-Picayune (New Orleans, LA)

Donna Shrum in Country Roads, When the French Quarter Was Italian.

Sicilians in Battle to Death. (1902, June 12). Times-Picayune (New Orleans, LA)

Fyi, Donaldsonville is in *south*east Louisiana, not northeast.

LikeLike

Thank you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Justin. I really enjoyed reading the above article. What really caught my attention was the area of Highland, Nee York. Reason being I am trying to research a family member who lived in Highland, NY. The name is Michael Ognibene with the spelling of Agnine. On the 1940 census Michael was an inmate in Highland, UlsterCountyNY. The Ognibene family is from Vallelunga, Sicily. I am wondering if there is a connection. I have a feeling that the names were changed once the children of Liborio married. Most of the clan remained in Highland. What are your thoughts. Have you come across any Ognibene connections. Thanks

LikeLike

I haven’t heard that name, no.

LikeLike