Morello brought together gangsters from Corleone and elsewhere in southern Italy to produce counterfeit money on a farm in New York.

In the summer of 1909, detective William Flynn sought the source of counterfeit bills flooding banks and businesses in several cities across the United States. He tied the counterfeiting operation to Giuseppe Morello’s gang by following one of the passers of bad bills, Giuseppe Boscarino.

Morello was counterfeiting as early as 1903, when the “barrel murder” victim, one of Morello’s “coiners,” Benedetto Madonia, was lured to his death. In 1906, Morello was producing small denominations of false American and Canadian currency on a farm in Highland, New York, across the Hudson River from Poughkeepsie. The initial printing attempts were made using plates created by Antonio B. Milone, a business partner of Morello’s, but they were of too poor a quality to use. Antonio Comito, a printer from Calabria, met the gang through Antonio Cecala, both members of the mutual aid society, the Sons of Italy. Comito testified that he was forced to replace Milone on the farm in Highland.

The Highland farm where the bills were produced was owned first by Salvatore Cina and Vincenzo Giglio, and then sold to Giuseppe Palermo in 1909. Palermo, from Partanna, and the wagon driver, Nicholas Sylvester, a reformatory alum of unknown origin, are of no known relation to any of the other counterfeiters.

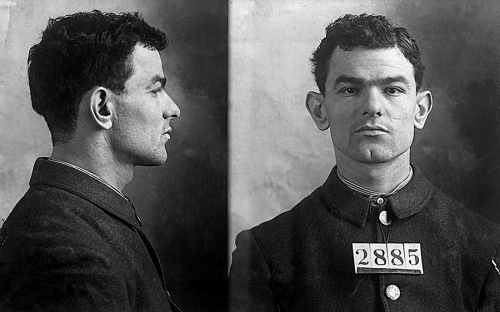

The first trial’s defendants included Giuseppe Morello and his brother in law, Ignazio Lupo.

- Giuseppe Callichio

- Antonio Cecala

- Salvatore Cina

- Vincenzo Giglio

- Ignacio Lupo

- Giuseppe Morello

- Giuseppe Palermo

- Nicholas Sylvester

All were found guilty and sentenced to the federal penitentiary near Atlanta.

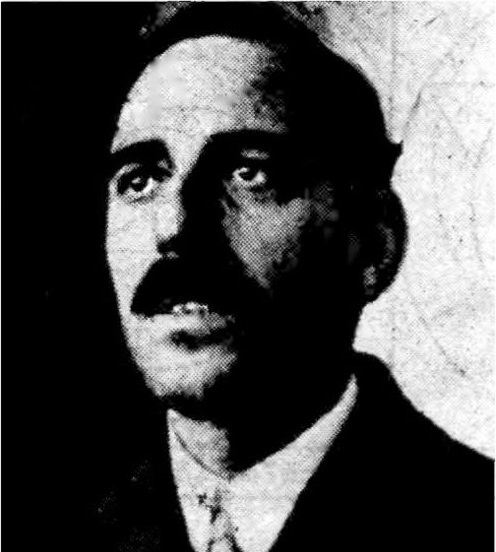

Antonio Cecala is called the other leading figure in the counterfeiting ring, alongside Morello, in contemporary news accounts. Jon Black at Gang Rule says that Antonio Cecala was also Corleonese, but I have not found his baptism among the records for Corleone available online, nor a marriage for his parents, whose names are known from Cecala’s naturalization record. The manifest of the Iniziativa tell us Antonio and his father traveled together, and that they were both barbers, but not the town where they last lived, or where they were born. (Antonio appears again on a manifest in 1930, traveling with Brooklyn boss Vincent Mangano.)

Critchley writes that Vincenzo Giglio was born in Santo Stefano Quisquina, arrived in New York in 1895, then went to Tampa with Cina. Cina had a reputation as a criminal in his native Bivona, through association with Vassolona, an infamous bandit, and had to flee Sicily. It’s not known how they came to be associates, or why the teenage Vincenzo was traveling with Cina, but they are said to have emigrated together in 1894. Naturalization records for Salvatore Ciona, in Boston, give a date in 1894, but I have not been able to find a matching ship. When he was incarcerated, in 1910, Giglio reported immigrating in 1895.

According to Black, Cina and Giglio are brothers-in-law. I found a marriage for Salvatore Cina and Rosa Giglio in Tampa in 1900, but the record does not give their parents’ names, and there are other Giglios living in Tampa at this time. Rosa Giglio, 18 year old daughter of Angelo, in the 1900 census, has a brother named Vincenzo, which would seem to be a clear match. Her brother is known from a 1904 manifest showing Vincenzo Giglio, a 24 year old (b. 1880) proprietor from Santo Stefano Quisquina, going to his father at the same address, Oak Street in Tampa, where Rosa and her father live, and traveling with his mother, Angela Provenzana. Rosa’s death record confirms that Angelo Giglio and Angela Provenzana are her parents’ names, also. But this Rosa died in Tampa 1918, and her married name was Militello, not Cina.

Other records point to Salvatore Cina and his wife, Rosa Giglio Cina, having two daughters in Tampa, and then moving to New York. It appears there is at least one other couple with similar names to Salvatore and his wife, who also lived in New York around the same time. The other Salvatore Cina/Sena/Cena swore he immigrated in 1905 and lived in New York continuously until his 1919 naturalization. In the 1920 census, Salvatore and Rosa Cina appear, alone, in ED 324 of Manhattan. An infant, Joseph, who died in 1922 may have been either couple’s child. The one who immigrated in 1905 applied for a travel passport six months after Joseph’s death.

Cina, who was part owner in the farm in Highland, and his wife had at least four children. The oldest, Carmela, was born in Tampa in 1904. Antonio Comito testified that Cina visited his farm with Ignazio Lupo and the wagon driver, Sylvester, in 1909. Cina was indicted, along with Lupo, Palermo, Calicchio, and Giglio, for making bad bills. He was sentenced in the first of the two counterfeiting trials in 1910, and paroled in November 1916.

Carmela, his daughter, married in New York City in 1926. In 1930, Salvatore appears in the census for Manhattan, with Rosa and three of their children: the oldest, Jennie, born in Florida, and the youngest, Peter, born the year Salvatore went to prison.

Critchley writes on page 69 of The Origin of Organized Crime in America that Giuseppe Callichio, who was described as an “elderly man” in 1910, was Cina’s godson. However, records indicate Salvatore Cina, born in 1875, was at least twenty years younger than Calicchio. In Black’s account, Antonio Comito, the kidnapped printer, met Cecala’s godson, Salvatore Cina. But again, this would be impossible, as Cecala was born the same year as Cina.

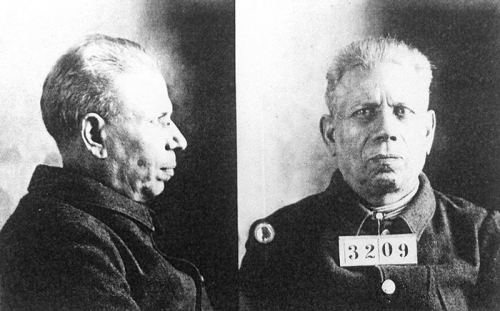

Callichio’s birth year and date of immigration are known from his appearances in federal censuses of the penitentiary outside Atlanta, in 1910 and 1920. The outlying record is the 1910 census, in which Callichio is said to be 53 years old (b. 1857) and a widower. In 1920, he is 68 (b. 1852) and married. He appears on a ship manifest in June 1906, traveling with a daughter. His age at emigration, 54, is a match for the 1920 census. The manifest indicates that he is originally from Puglia, and intends to join his brother in Utica, New York. As well as appearing in the prison in Georgia, the federal census shows Giuseppe Callichio with his family in Oneida, New York in 1910.

A second trial, held two weeks after the first, found at least seven more of Morello’s counterfeiters guilty, including Giuseppe’s half-brother, Nick Terranova.

- Giuseppe Armato

- Giuseppe Boscarino

- Luciano Maddi

- Domenico Milone

- Nick Terranova

- Leoluca Vasi

- Pasquale Vasi

Except for Maddi, whose origins are unknown, and Boscarino, who I’ll say more about below, the defendants are from Corleone. Also from Corleone, the LaSalle brothers, Steve and Calogero, were arrested in connection with the counterfeit operation, but I have not found any evidence of indictment. Likewise Antonio B. Milone, Domenico Milone’s third cousin, and the first printer in the Highland venture. Domenico, along with Boscarino, Maddi, Armato, the Vasi brothers, and Nick Terranova, were charged with having and passing the counterfeit bills.

If Cecala was the human connection among half the defendants in the first trial, the center of gravity among the Corleonesi was Leoluchina Armato, the sister of defendant Giuseppe Armato. In 1905 she emigrated with Giuseppe Lagumina, who is her nephew by marriage, and her second cousin, once removed, as well as being a Morello associate. Lagumina’s uncle, Giovanni Rumore, was also a known Morello gangster. (Armato and Rumore were also related: they are second cousins.)

Leoluchina’s brother shared an apartment in New York with brothers Leoluca and Pasquale Vasi. Upon their arrest in 1909, thousands in counterfeit bills were recovered from the apartment. Leoluca Vasi was married to a niece of Domenico Milone. And Domenico was married to Giuseppe and Leoluchina’s sister, Giuseppa Armato. When Flynn had Giuseppe Boscarino, a sixty year old (b. 1849) man from Corleone, followed by detectives, he was seen entering the wholesale grocery store once once owned by Ignazio Lupo, at 236 E 97th St, and at the time owned by Domenico Milone and Luciano Maddi.

Jon Black writes that Giuseppe Boscarino was born around 1850 in Corleone. According to Flynn, Boscarino immigrated in 1890 and was a known associate of the “Black Hand” in New York’s Little Italy. One of his close friends was Don Vito Cascio Ferro, who would become powerful enough to disrupt local leadership of the Fratuzzi in Corleone, in the first decade of the twentieth century. I have not been able to confirm Boscarino’s birth or immigration. There is at least one Boscarino/Boscarelli family in Corleone, distinguished by their address (they live near the most important families in town, in 1834) and honorifics: they’re called “don” and “donna” in Church records. There is a baptismal record that appears to be a match for Giuseppe Boscarelli, in December 1849 in Corleone, but that child died at age three.

Antonio B. Milone immigrated in 1889 with his father, Alberto. Milone and Gaetano Reina, one of Morello’s captains, are second cousins. In 1903, Milone became an officer in Giuseppe Morello’s new building cooperative. In 1907, the Banker’s Panic wiped out the Co-op. Antonio married a woman from Milan, the following year.

Comito gave testimony against his captors, and avoided prosecution. Despite having been identified as an integral parts of the counterfeiting operation, Antonio Milone and Giuseppe Boscarino both avoided prosecution.

Cool history!

LikeLike